When the jackpots are big enough, we see money pouring in. But ‘big enough’ keeps floating higher, and the number of players is not growing significantly. If we want to engage people to play more money more often, we need to give them better value. I discuss how to do that, in NASPL Insights April 2020.

Category: design features

what the game should do

Slowly expanding territory of lottery games

Thinking about lottery games structurally helps us to understand how true innovation might happen. Players, however, have their own ways of thinking about games – notions not to be corrected, but simply understood as we offer new things. The folk categories might have to twist or expand to accommodate things like ‘Fast Play’ -i.e. instant games that print while we watch. This and other innovations appear in NASPL Insights December 2019.

A Long Perspective on Draw Games

Draw games in North America show the marks of their making, mostly in the 1980s. Running these games is a performance that plays to a dwindling audience. Yet there may be ways to engage people in new modes, as I suggest in NASPL Insights April 2019.

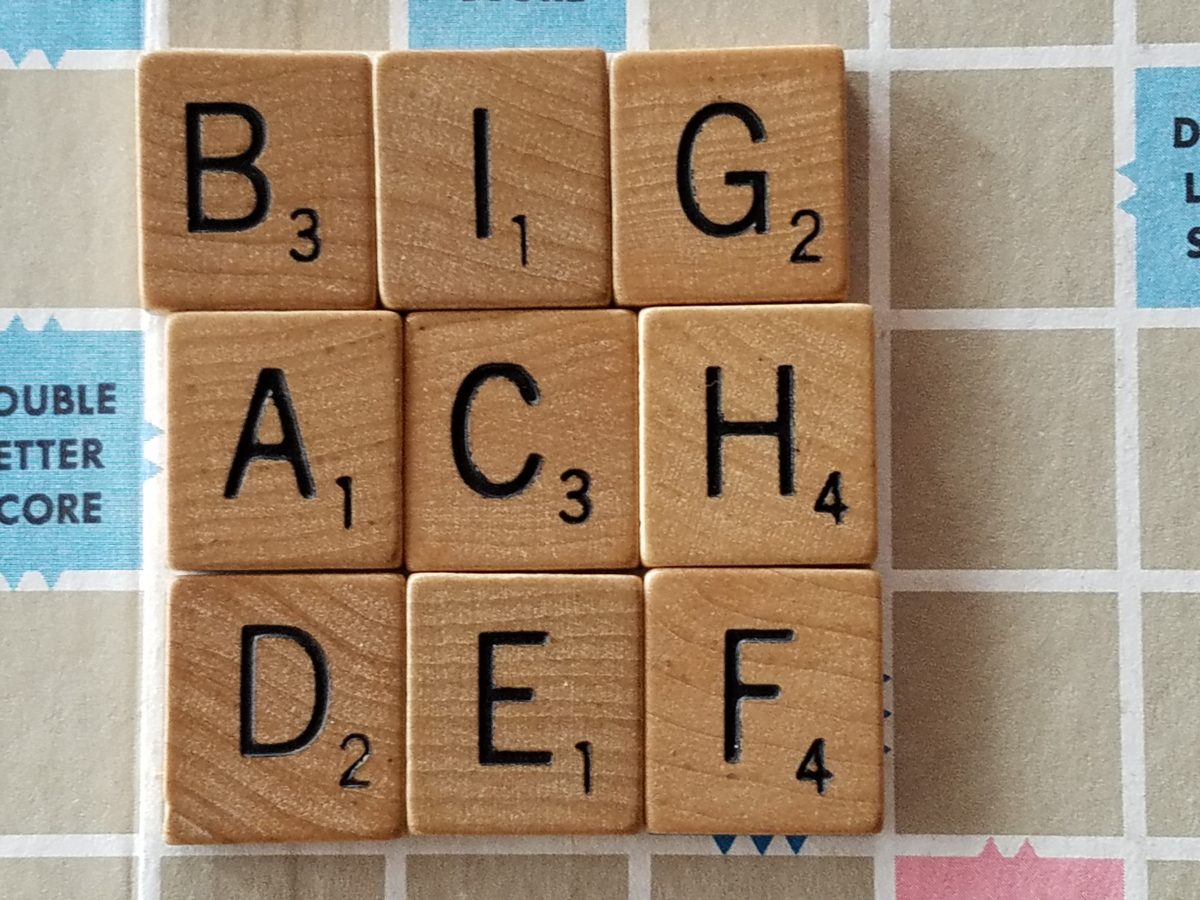

Real Gains through Simulated Play!

A new look for lottery

And I mean a new ‘looking for’ as well as a new ‘look’. Rather than sticking to game mechanics that have simple, obvious math defining the outcome probabilities, let’s ‘look for’ play value first. Get the probabilities by numerical simulation (teaching a computer to play). The grid above could be worth significant money, in the game I describe in NASPL Insights February 2019!

Betting Randomly on Sports: New Lottery Territory?

People are publicly passionate about sports, as about little else. Where they bet money on sports, the collision of passions and skill can support a big business. Lotteries, accustomed to running games of pure chance, face a steep learning curve if they get involved in sports betting. But there is potential to use a sporting event to determine the outcome of a game of pure chance- if the player bets randomly. How can lotteries develop this opportunity? I explore this question in NASPL Insights September 2018.

Risky Business – Time for Insurance?

Historically, state-sponsored lotteries have relied on the sheer volume of transactions, achieved through their monopoly status, to make the risk of paying big prizes reasonable. However, these advantages may be absent when a new game is started. Other businesses have developed risk-sharing mechanisms, including insurance against specific risks. ‘Synthetic’ lotteries like Lottoland have shown these can work in gaming. There maybe something to learn here, as I discuss in NASPL Insights August 2018.

Which Keno?

Within Keno, players can put their money on any of several very different wagers. They all have the same very plain look and feel, yet some get a lot of action while others get little. What can we learn from this? I compare the likely winning experience of different wagers and identify what seems to be engaging the players in Michigan, in NASPL Insights June 2018.

Why Keno?

Keno, a traditional game with origins in Asia, is a busy game: from a huge cast of characters (numbers 1 through 80) it scrambles 20 across the stage every drawing. It looks complicated for the player, with several different types of bet available. And yet, it thrives better than most draw games in settings where there is an opportunity to play every few minutes. Why? The math of the game supports the hopeful intuitions of players, as I show in NASPL Insights April 2018.

Go ahead, call us “the Lotto”…

The Lotto game, developed in the middle of the 20th century, was a big improvement over earlier games, but needed the scale that only government monopolies could at that time provide. Now, state lotteries offer big and small versions of Lotto under a variety of names. When people call us “the Lotto”, they may be recognizing that this is our particular franchise -not a bad thing, I suggest. NASPL Insights April 2016

Outlook for the Big Games in 2015

NASPL Insights December 2014, I assessed the behavior of the Powerball and Mega Millions games in the eleven months since California joined the Powerball game. I found that while sales at jackpots below $100 million had remained fairly steady, the sales response to jackpots approaching $300 million was less than half what it had been during the “base period” between Feb 2012 (when Powerball raised its price to $2) and April 2013 (when California joined). I went on to project the probability distribution for jackpots greater than $300 million in the coming year. The difference between the games was stark: Powerball was more likely than not to have three or more such events, while Mega Millions was more likely than not to have no more than one.